Taking

Science to the Masses

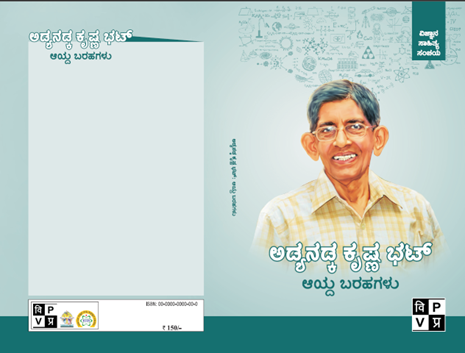

Remembering a

noted Kannada science communicator

Prof Adyanadka Krishna Bhat

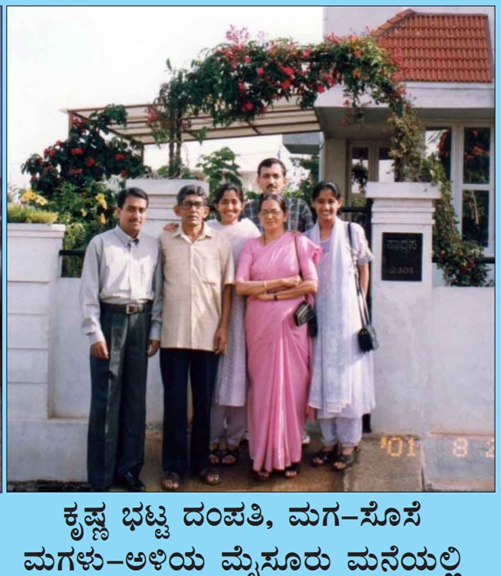

[Vineela, the Kannada title of the biographical work on Prof A K Bhat pictured above, compiled and edited by his younger brother Mr A Ramachandra Bhat, signifies a special hue of blue color associated with clear skies that was very dear to Prof Bhat. It is also the name given by him to his grandson residing in the USA]

His message of hope and optimism: “Lonely we never are when 100 billion earthlike planets are there without our knowing them. Let us move on to know each other.” (From one of his emails)

The movement for popularization of science in Kannada, pioneered by the

likes of Prof J R Lakshmana Rao and others, was greatly enriched by another

noted contemporary science communicator, Prof Adyanadka Krishna Bhat. This is in

memory of this gentle, soft-spoken, amiable, self-effacing, behind-the-scenes operator

who believed in living up to the responsibilities of his profession and in a sense

of duty to society, besides a strong love for communicating science to all

classes of people. It is also in recollection of my own memorable association

with him. By an unintended coincidence, I am posting this on his 8th death

anniversary.

The flier reproduced below gives

a crisp summary of the life and work of Prof Adyanadka Krishna Bhat in

Kannada, which I have sought to elaborate for my (English) readers in this article

(15 Mar 1938 was his birthdate):

https://youtu.be/3E20thVs7GE?si=-7HPcMvRxDtvDopV – Part 1

https://youtu.be/WwAwSrHjKOs?si=Iq1qm9lcGTcW5Knk – Part 2]

Looking Back

Rotary Brahmanda event

I had known a great deal about Prof Adyanadka Krishna

Bhat (I will shorten his name to AKB in the rest of this article) through Prof J R Lakshmana Rao the subject of my

last blog article, during my frequent contacts with the latter. I had also

heard about him from close mutual associates like Prof G T Narayana Rao and

others. I first met AKB only much later, during a symposium on Astronomy and

Space Sciences for schools in Mysore, planned and overseen by my long-time protégé,

then student-leader Chiranjeevi, under the sponsorship of Rotary Midtown Mysore

(RI Dist 3180) and active participation of ISRO Bangalore on 23 July 2011. As could be expected, I was drawn immediately

to AKB for the same simplicity, friendliness and scholarship that characterized

Prof JRL. We were both speakers in the

seminar along with a number of other luminaries. Here is a group photo taken on

the occasion:

Here is the

programme sheet, with a candid picture of AKB taken while he was addressing a

large gathering, mainly of school students, on the occasion:

The words ‘ancient times‘ are taken to mean the times

of the ancient urban civilizations that evolved in various parts of the world. References

are made to Sumeria and Babylon (of fertile crescent), Maya (of Central

America), Egypt, China, India and Greece. The observations made during the

millennium BC continued to have their influence during the millenniums after

Christ as revealed in the works of Indian Astronomers.

…The circumstances were conducive for night sky

watching with the mental makeup of mythology and religion… The knowledge of the

cycle of eclipses, full cycle of Venus, the annual movement of the Sun, …..

The absence of theory might have limited the advance

of knowledge in ancient times. The scientific methods could have been the

exclusive privilege of a particular class of the population. Efforts to remove

these stumbling blocks took place after the scientific revolution led by

Copernicus and Galileo in the 16th -17th centuries.]

In a later session, I had spoken on the theme of

‘Eclipses’, focusing largely on my own experience of observing total and

annular solar eclipses till that time and my plans for such efforts in the

future, particularly about the next two total solar eclipses due in 2016 and

2017, in Indonesia and USA respectively.

Doomsday 2012 Symposium

The next time I met AKB was at a symposium and Q&A

session in at the Vidyavardhaka Engineering College, also in Mysore, to which student-leader

Chiranjeevi had invited both of us as guests on 5 May 2012. The subject of the

symposium was ‘Doomsday 2012’, the popular fear psychosis associated with the

impending ‘end of the world’ scenario as implicitly ‘predicted’ in the ancient

Mayan calendar, one of the recurring predictions since time immemorial about the

end of civilization on the admittedly fragile planet. After we both had debunked

the notion with ample scientific arguments from both the astronomical and physical

points of view*, we faced a volley of questions from a rather puzzled student audience.

We had not expected such credulity to something so patently absurd as an

existential threat implied in a complex calendar system prevalent in a

civilization otherwise known for its contributions to astronomy. While answering these questions, I had a hard

time matching AKB’s unperturbed calmness and disarming sense of humor, so much

a part of effective communication.

[*AKB had come fully armed for the occasion and had

shared his ideas with me in advance. In

his email response to Chiranjeevi, he had outlined the key points of our

presentation as follows:

“The discussion/debate may take place by going through the following themes:

2 Roles played by personal religion and the individual world view

3 Use of modern technology in spreading falsehoods

4 Actual failure of the predictions and face-saving steps

5 ‘Arguments’ for the latest prediction

6 The false premises upon which the ’prediction’ is built up

7 Vested interests that nurture the doomsday situation.

8 The misuse of modern communication as well as scientific jargon.”]

The End

During our conversations at the Brahmanda symposium,

AKB had expressed a serious interest in joining me on my next total solar

eclipse expedition to the Central Sulawesi Province of Indonesia, where the

event, due on 9 March 2016 could possibly be observed best. He had confirmed this when I next met him once

more, at his home at Mysore sometime later. However, my email to him, apparently

sometime in August 2015, laying out my detailed plan for the Indonesia visit

brought the following terribly sad response on 5 September:

“Your enthusing mail is truly infectious. Unfortunately,

due to ill health I am confined to the indoors in my daughter's house at Gokak.

But for this disability, probably I would have joined you. I remember your

speech at the Rotary (event) three years ago, when you had explained your plan.

After a heart attack a year ago, I had my eyesight impaired. But my daughter's

timely help has helped me to regain it to some extent. But my immobility has

become a great handicap.

Wishing you all the best, I am your sincerely, AKB”

In my

spontaneous reply, I said in part:

“I

am greatly distressed to hear all this from you and hope your stay in Gokak is

otherwise comfortable. Compared to your present circumstances, I seem to

be immensely better off and capable of the eclipse adventures I have planned

for the next two years. I wish you could indeed have joined me in the

next one in Indonesia. I will of course be all alone, just as in 2009 in

China! But this loneliness is of a profoundly edifying kind and something

I have even enjoyed! I do indeed look forward to it.

With

best regards, SNPrasad”

Below is a picture of AKB at work in his

characteristic style in November 2016:

Not long after that, on 19 December 2016, Chiranjeevi

brought me the sad news of his passing away at Gokak. We had a hard time coping with his loss so

soon after such a memorable association with him.

After Chiranjeevi read my latest blog article

enshrining the memory of Prof JRL, he lost no time in convincing me that I

should memorialize AKB in a similar manner, and for similar contributions to

the cause of effective science communication in Kannada. Here is my feeble attempt to do so.

AKB in Real Life

I would now like to shift focus on to the life and

work of this eminent person in real life.

Education

Born on 15 March 1938, at Adyanadka in Bantwal Taluk

of Dakshina Kannada district in Karnataka, AKB had his early education in the

same town, and high school education in Vittal and Puttur during 1951-54.

Thereafter (in 1954-56), he studied the Intermediate course in science at the MGM

College Udupi.

At that time Udupi was part of the province of Madras,

and it was not uncommon for students from the coastal belt to seek admission in

higher educational institutions in Madras city. With the required credentials

and support from a family friend AKB shifted to Madras (later to be named

Chennai) for his higher education, quite a long way away from home. In 1959, he obtained his BSc (Hons) degree in

Physics from the famous Presidency College after a three-year sojourn. One of the oldest institutions for higher

education in the country, this was also the institution in which India’s only

Nobel Laureate in science, C V Raman, had studied and done some notable

research on diffraction of light even as a teenager. I wonder how AKB felt when he stepped into

the portals of an institution with such a distinguished background.

A year later, in 1960, AKB earned his MA degree in

Physics from the same institution, something that C V Raman had also done in 1907.

Rather curiously, the master’s degree, even in science, was designated MA and

not MSc in those days, a throwback to the practice prevalent in Britain.

An Interlude - AKB and I

My acquaintance with AKB was short, but highly edifying.

Without sounding too presumptuous, I discovered

many things in common with him as I began to write this article. Here are some of these commonalities:

- Born in 1938, six months apart, in a rural environment

- Growing up under severe financial constraints and a very harsh life in student days

- Extensive reading, of both literary and scientific works

- Securing admission in prestigious higher education institutions through merit-based selection

- Higher education in Physics – BSc (Hons), 1956-59; MA /MSc, 1960

- Pursuing studies in Physics as an afterthought

- A forgettable performance in the final degree examination

- Starting professional careers as college physics teachers in 1960, and staying so till retirement (1996/2000)

- Observational Astronomy as a major hobby, and as an integral part of the profession

- Similar experiences and excitement with special astronomical events like comets, solar eclipses, night sky objects, etc., sharing with students, teachers and common people in a variety of ways (see representative picture below)

- Commitment to popularization of science and the inculcation of a scientific temper, spirit of inquiry and humanism

- A passive, but uncompromising brand of rationalism that doesn’t come into direct conflict with any dogmatic belief systems

Promoting observational astronomy

Family life

AKB was born into a highly unconventional family (not observing

rituals like daily puja, madi/mailige, thithi, etc.), the

exact opposite of a traditional Brahmin family of those days, in the village of

Adyanadka, in the Udupi District of Karnataka. The region is known for its rich

cultural and spiritual heritage, which had a great bearing on his upbringing

and early education. He was the eldest in a large tight-knit family most of

whose members can be seen in the picture below, with AKB standing fourth from

left in the back row. His younger brother and author of the biographical work Vineela

is to his right. As the virtual head of this group, he had to discharge a

variety of responsibilities, including financial ones in the formative years.

He was always held in high respect from both within and outside the group.

A happy family on the beach in the olden days

The picture below shows him enjoying a precious moment

with his grandson at play:

Professional Career

Teaching

After his higher education in Madras, AKB worked initially

for two years as a Demonstrator in Physics at the MGM College, Udupi and then

as a Lecturer in Physics at St Philomena’s College in Puttur during

1961-63. Thereafter, he moved to Vijaya

College, Mulki, starting as a lecturer, until his retirement as Professor and HoD

[1963-96]. He believed that strongly “the work of a teacher does not stop with

teaching the students in the class - but also to keep himself engaged in study

and to give the benefits of his study to non-students also.” He lived up to

this simple motto all his life.

Science Journalism

From 1961 onwards, AKB contributed popular science

articles to periodicals such as Vicharavani, Sudha, Pustakaprapancha and

Kasturi. He was the chief editor

of Vijnanaloka, a monthly popular science journal in Kannada for seven

years, during 1966-70 and then, 1974-77.

His long association with the popular monthly science journal Balavijnana

began in 1983, initially as member of the editorial board, and then as its

chief editor from 1989 to 2000.

Encyclopedia and Science Dictionaries

- During 1970-74, AKB was the science editor of Jnana Gangothri (a seven-volume Children’s Encyclopedia in Kannada.

- During 1974-79, he contributed to Kannada Vishwakosha, a general cyclopedia in Kannada published by the Mysore University.

- Edited Sudarshana, a general encyclopedic work on Dakshina Kannada district published by Vijaya College, Mulki, in the form of a felicitation volume to Dr T M A Pai, in 1977.

- He co-edited the English-Kannada Science Glossary published by the KRVP in 1990.

- He later served as a consultant to Navakarnataka Publications in Bangalore to several of its science related works.

Science Organizations

AKB was associated with a number of organizations devoted to the promotion and cultivation of science. Principally, these are:

- Founder membership of Vijnana Pratishsthana, Dakshina Kannada (1966)

- Founder member of KRVP* (1960) and its vice-president during 1993-95

- Member of the District Council for Science & Technology, Dakshina Kannada since its inception (1991) to 1996

- Life Member of the Indian Association of Physics Teachers

- Past president and member of the Mangalore University Physics Teachers’ Association

Below is a picture that is self-explanatory:

AKB is seen sitting fourth from right; Prof J R Lakshmana Rao is seen

sitting fourth from left

Another picture below, associated with the KRVP Mysore Center, shows AKB and several other of his KRVP associates:

AKB is seen sitting second from left, Prof J R

Lakshmana Rao sitting fifth from left and Prof G T Narayana Rao sitting third

from the right

Field Activities

- Extension lectures on science topics in rural areas under the auspices of Prasaranga of Mysore University since 1963

- Popular science talks supported by projected slides in schools, colleges and universities

- Extensive Observational Astronomy activities for students and the general public, many using portable optical telescopes

- Organizing Jana Vijnana Jatha (taking science to the masses movement), especially in Dakshina Kannada district

- Organizing science exhibitions in educational institutions (1965-95)

- Organized and participated as a resource person in several workshops for science writers, students and teachers under KRVP and other voluntary organizations

- Broadcasting night sky commentary, popular science talks, etc., through All India Radio stations

- Organized Khagola Yana, popular astronomy program on the eve of the total solar eclipse of 1995, which he also observed with a team of students in Alwar, Rajasthan. Also, similar activities during the total solar eclipse of 1999 in Bhuj, Gujarat

- Worked as a resource person in the Science Popularization Workshop on ‘The Emergence of Modern Science – Golden Decade of 1985-1905’ organized jointly by NCSTC and KRVP in 2000

Publications

· Original writings

- Gaganayuga (Kannada) 1964

- Gravitation – from Galileo to Hoyle (English) 1965

- C V Raman (in Kannada, English & Hindi) 1973

- Story of Man (English) 1977

- Manushyana Kathe (Kannada) 1977

- Muthulakshmi Reddi (Kannada) 1978

- Isaac Newton (Kannada) 1979

- Manushyana Vamshavali (Kannada) 1980

- Introductory Physics (English – coauthored) 1977

- Poorna Soorya Grahana (Kannada) 1995

- Bellichikke (Kannada) 1995

- Namma Vaatavarana (Kannada) 1998

- Nava Vijnanada Udaya (Kannada) 2001

- Physics matthu Einstein (Kannada)

- Kishora Vijnana (Kannada)

Translations (English to Kannada)

- How to build a telescope, for KRVP

- Halley communications, for KRVP

- Understanding Science, for International Book House

- Raman and His Work, for the National Book Trust

- Wind Energy, for the National Book Trust

- Weather Weapon, for the National Book Trust

Here are the title pages of three of the books written

by AKB in Kannada:

- In 1979, AKB received the Karnataka Rajya Sahitya Academy award for his book ‘Manushyana Kathe’ under the children’s literature category.

- In 1992, he was bestowed an honorary fellowship of the Academy of General Education in Manipal for distinguished and meritorious service in the field of popular science.

- AKB was awarded the prestigious NCSTC National Award for the best efforts in popularizing science during 1990-94. The award was conferred on him appropriately on National Science Day, on 29 Feb 1996. Here is a copy of the citation he received on the occasion as it appears on the biographical work by his brother cited earlier:

Below is a picture of AKB with his richly deserved national award:

Tributes from a close friend and admirer

One of the people who

knew AKB intimately is Mr Kollegala Sharma (see picture below), a

renowned fellow science communicator who also writes mainly in Kannada, and widely

involved in taking science to the masses. He responded to my special request with a

detailed write-up which brings out the human side of AKB as much as his

professionalism and commitment to his cause. Here is an abridged and edited

version of what I received from him:

Mr Kollegala Sharma

For me he was a mentor, a teacher, a friend and more than anything a wonderful human being who personified the values of his time. I met him forty years ago when Indian science communicators embarked on Bharat Jan Vijnan Jatha, a first of its kind public science movement in India. The movement aimed to mobilise people of all walks of life to the importance of science, and scientific temper. The year was 1986. I was a research fellow, and curious about science writing. AKB was coordinating the Jatha, a walk across the west coast of India. I wrote a post card indicating my interest in the movement. A few days later I received a reply, on a post card, asking me to visit him in his place. It was just 30 km away, and the letter indicated that he had read the few articles that I had written by then. I met him in his home, and enjoyed a sumptuous hospitality. His wife, Saraswathi Akka for me, is a great cook too.

He could have stopped at

writing a reply for my query. But aware

that I was also a writer he wanted to meet me and collaborate. That was my first brush with this gentle,

kind but generous personality. Later

there were several occasions when we participated together in workshops, in

meetings and for tea at his house. I was

a generation younger to him, but whenever I spoke of any idea, he listened

carefully. I was cautioned about the

risks, but encouraged to try.

Whenever travelled

together he would insist on paying his part of any expenditure. If I laughed it off, he would say that he is

paid by the organisers, and he would not like to claim reimbursement without

paying for the expenses. He never rode a

scooter or car, not even a bicycle. He

would travel by public transport, and mostly in the general class. He made it a point to walk the distance, if

he could, and only in dire needs would he hire a rickshaw. Many times, when he rode pillion on my

two-wheeler, I could feel his discomfort.

It is a surprise that he

had a huge student following. Surprise

because he never raised his voice. He

was very soft spoken. But his writings

were crystal clear. As an editor, he

taught us life lessons. A 500-word essay

would be marked with at least 10 comments when he edited - questions on

clarity, factuality, language, use of words, etc. Never on any style. And these comments were not written

casually. He would sit at his table with

a pile of reference books, and then edit.

Such a disciplinarian, he would read, write, edit at his table. Never in the bed.

One instance remains

etched in my memory. I was preparing for

a lecture on issues with translating science and technology texts from English

to Kannada. I would highlight the deficiencies

of target language with an example from Richard Feynman’s writings. He used the word Revolution as a pun in a

lovely sentence. I argued that Feynman’s

pun is not translatable because in Kannada there was no word that had the twin

meanings Revolution had. He concurred,

but reluctantly. He was not ready to

accept that an ancient language like Kannada had such difficulty.

A fortnight later, I

received a call. The moment the landline

phone rang, I knew it was only AKB. He

was not very comfortable with cell phones.

He was the only caller to my land line.

It was about the word Revolution.

After our discussion, he had diligently researched upon the word while I

had forgotten the whole episode itself.

He had found that there was indeed a word – Krantha - in Kannada that

had the twin meanings of Revolution – of planetary motion and of social

change. Only that over time, the word

went to oblivion because it was not used much.

The dynamism of language had killed the word. AKB was serious with every word he said, and

in his act.

He was a regular reader

of my column in Kannada Prabha, and would without fail give his feedback, on

the plus and minus of every writeup. He

never ignored any writing because it was from a novice, or a student. Every writeup, be it of experienced writers

or young experimenters, he would edit with the same seriousness. No wonder he created a wealth of literature

that stands the test of time. He was as

unique as his writing which had the unmistakable flavour of coastal Kannada and

yet appealed to all Kannadigas.

Chiranjeevi had intended to visit AKB’s

wife and daughter at the latter’s residence in Gokak, his last haven, to pay

his respects and convey my intention to write this blog article. Then, he came to know that they were actually

due to pass through Mysore on December 15. He grabbed this opportunity to meet them at

the Mysore railway station during the period of train stoppage. He showed them

a draft of this article under preparation and obtained some valuable feedback.

During their meeting, it came to light that AKB’s wife had played a vital

behind-the-scenes role in much of her husband’s writing outside of his work

with Bala Vijnana. She acted as a

scribe, writing down all that AKB dictated and then giving shape to the final

version of the document, clearly with her hidden stamp of finality on it. In the process, she has contributed more to AKB’s

published works than is commonly known. This

discovery is a fitting finale to this article.

Chiranjeevi also learnt that AKB’s

younger brother, who authored his published biography and conducted an extensive

audio interview with him as quoted earlier, had a major influence on him too.

In any case, this article would not have been possible without the inputs we

received from him.

Here is a selfie of Chiranjeevi, with

AKB’s daughter Deepthi and wife Saraswathi:

A Eulogy

Behind every successful enterprise there are many unsung

heroes. It is they who hold the threads of society together. AKB was undoubtedly

one such hero. He never sought any

recognition or reward for his contributions to societal causes. As his daughter

so aptly put it, he valued the ‘inner scoreboard’ more than the outer one.

Also, he was never seen angry anytime; anger was an emotion he associated with

the mentally weak.

As my parting memory of such an inspiring human being,

here are three faces of him in different moods that I think describe his persona

lucidly:

The three faces of AKB