Einstein and

IYQ25

Pioneers of Quantum Theoretical

Physics

Part 2

"Einstein

was not merely a scientist; he was a revolutionary thinker who reshaped the

very foundations of our understanding of the universe."

– Michio Kaku, describing Einstein’s

transformative influence.

UNESCO has proclaimed 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (IYQ). This year-long, worldwide initiative will celebrate the contributions of quantum science to technological progress over the past century, raise global awareness of its importance to sustainable development in the 21st century, and ensure that all nations have access to quantum education and opportunities.

In celebration of IYQ25, this series of articles focuses on the key personalities of quantum theoretical physics and their work – ten of the greatest, from Planck to Feynman. The first article (see here) focused on the background to IYQ25 and the advent of quantum theory through the pioneering work of Max Plack. This is the second one – on Einstein and his contributions to the quantum revolution.

Einstein and his place in history

In 1999, TIME magazine enshrined

Albert Einstein as the Person of the Century (see picture above),

recognizing his unparalleled influence on science, philosophy, and global

history. His selection over other notable figures, such as Gandhi and Roosevelt,

reflected his profound impact on our understanding of the universe. Einstein's

contributions were deemed timeless and universal, making him the most fitting

choice for the extraordinary honor.

A byword even outside the realm of science and one of

the most celebrated personalities in human history, Albert Einstein (1879 – 1955)

revolutionized our understanding of the most fundamental concepts of science, including

matter and energy, space and time, gravitation, etc. His achievements and their

impact on human knowledge are unparalleled since the times of Isaac Newton (1643

– 1727). His contributions span the development of special and general

relativity, quantum theory, statistical mechanics, and cosmology. While he is

most famous for the theories of relativity, his seminal work in quantum physics

laid the foundation for many aspects of modern quantum science, yet he remained

deeply skeptical of its philosophical implications, particularly the

probabilistic and observer-dependent nature of the Copenhagen Interpretation (to

be discussed in greater detail in future articles of this series).

Here we explore Einstein’s life, his contributions to

quantum physics, and his unhappiness with the dominant interpretation of

quantum mechanics.

First, let us merely summarize Einstein’s notable

contributions to other areas of physics before focusing on his

pioneering work in quantum physics.

1. Special Relativity (1905)

In his annus mirabilis (‘miracle year’) of

1905, Einstein formulated the theory of special relativity, which redefined our

understanding of space and time, as also of matter and energy. It had just two

key postulates that were to ‘transform our understanding of the universe’ as

Michio Kaku put it – on both microscopic and macroscopic scales. They were:

(b) The speed of light is constant in all inertial frames.

[An

inertial frame is a frame of reference in which the laws of inertia, i.e.,

newtons laws of motion, are valid. The Earth as a frame of reference is an

example, although not in the strictest sense of its definition.

While

the first postulate seems to be all that one might expect from common sense,

the second is certainly not so, leading to several counterintuitive situations that

could be experimentally validated.]

They led to groundbreaking results such as time

dilation, length contraction, and the famous energy-mass equivalence equation:

E = mc2

[This essentially means that a small amount of mass m can

be converted into a large amount of energy E under the right conditions, such

as in an atom bomb or nuclear reactor. The speed of light c has the value 2.9979

x 108 m/sec.]

2. General Relativity (1915)

Einstein extended relativity to include gravitation, showing

that gravity is not a force (as Newton described it) but rather the curvature

of spacetime caused by mass and energy [We live in a four-dimensional world,

with three dimensions of space and one of time]. This was to pave the

foundation for modern Cosmology and our understanding of the macroscopic universe.

Without going into any explanations, his results can be neatly summarized mathematically

in the form of a tensor equation as:

Here, the Einstein Tensor Gμν represents the curvature of spacetime due to gravity,

the second term is the cosmological constant introduced by Einstein to allow

for a static universe (his ‘biggest blunder’!), Tμν is the energy-momentum stress tensor. G is the gravitational

constant and c, the speed of light in vacuum.

[This is not the place for details of what this is and

how this was arrived at, except to observe that Einstein’s Nobel Prize winning

contributions on the photoelectric effect and the photon concept pale into relative

insignificance compared to his theories of Special and General Relativity.]

In contrast, the much simpler, and certainly more

famous, Newton’s law of gravitation can be stated as:

Here, F is the gravitational force

between two objects of masses m1 and m2, separated by a distance r. The gravitational constant

G has the value 6.6743 x10-11 m3 kg-1 s-2.

3. Brownian Motion (1905)

Einstein provided a mathematical explanation for

Brownian motion (the random movement of particles in a gas or liquid caused by

collisions between particles and the atoms or molecules in the fluid,

observable through a microscope), offering strong evidence for the existence of

atoms and molecules. This work helped confirm kinetic theory and classical statistical

mechanics. Jean Perrin’s

experiments on Brownian motion, which won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in

1926, provided the supporting empirical evidence.

4. Stimulated Emission and the basis for Lasers (1917)

Einstein introduced the concept of stimulated

emission, a principle underlying the functioning of lasers that were operationally

realized decades later. He predicted that atoms could emit photons when

influenced by external electromagnetic radiation, a fundamental idea later used

in laser technology.

Einstein’s Contributions to Quantum Physics

The Photoelectric Effect and the Birth of Quantum

Theory

The photoelectric effect, first observed by Heinrich

Hertz in 1887 and later studied in detail by Philipp Lenard* and others,

involves the emission of electrons from a material when it is exposed to light.

Classical physics, primarily based on Maxwell's electromagnetic theory and the

wave theory of light, faced insurmountable difficulties in explaining the

experimental observations of the photoelectric effect. These were ultimately

resolved by Einstein's photon theory in 1905, which generalized the concept of

quantized light energy first employed by Planck (see here).

[*Notwithstanding his Nobel Prize winning work that led

to profound consequences in the hands of Einstein, Lenard was a rabid opponent

of almost everything that Einstein did and stood for. He was also a staunch

supporter of Hitler and champion of ‘Nazi German Physics’.]

Experimental Background

In experiments on the photoelectric effect, light is

shone onto a metal surface (see diagram of an experimental setup below), and the properties

of the emitted electrons (called photoelectrons) are measured. Key observations

include:

1. Threshold

Frequency: Electrons are only emitted if the light frequency exceeds a

certain threshold, regardless of the light's intensity.

2. Instantaneous

Emission: Electrons are emitted almost instantaneously when the light

strikes the surface, with no detectable time delay.

3. Kinetic Energy

of Electrons: The maximum kinetic energy of the emitted electrons depends

on the frequency of the light, not its intensity.

Higher-frequency light results in higher-energy electrons.

4. Intensity

Dependence: The number of emitted electrons increases with the

intensity of the light, but their maximum kinetic energy does not.

Difficulties faced by Classical Physics

Classical wave theory of light, which treats light as

a continuous electromagnetic wave, could not adequately explain these

observations:

1. Threshold

Frequency: According to classical theory, the energy of a wave is

proportional to its intensity (amplitude squared). Thus, even low-frequency

light should eventually emit electrons if the intensity is high enough.

However, experiments showed that no electrons are emitted below a certain

frequency, regardless of intensity.

2. Instantaneous

Emission: Classical theory predicted that electrons would need time to

accumulate energy from the light wave before being emitted. However,

experiments showed that emission occurs instantaneously, even at very low light

intensities.

3. Kinetic Energy

Dependence: Classical theory suggested that the energy of emitted electrons

should depend on the intensity of the light, not its frequency. However,

experiments showed that the kinetic energy of electrons depends on the

frequency, not the intensity.

Einstein's Photon Theory

In 1905, Einstein proposed a revolutionary explanation

based on an extended application of Max Planck's quantum hypothesis. He

suggested that light is composed of discrete packets of energy called photons,

each with energy E = hν, where h is Planck's constant and ν

is the frequency of the light. This theory resolved the difficulties as

follows:

1. Threshold

Frequency: Electrons are emitted only if the energy of a single photon hν

exceeds the work function φ of the material, which is the minimum energy

required to eject an electron. This explains why light below a certain

frequency cannot emit electrons, regardless of intensity.

2. Instantaneous

Emission: Since energy is delivered in discrete packets (photons), an

electron can be emitted immediately if it absorbs a photon with sufficient

energy. No time delay is needed for energy accumulation.

3. Kinetic Energy

Dependence: The maximum kinetic energy of the emitted electrons is given by

Kmax = hν - φ. This directly links the energy of the

electrons to the frequency of the light, not its intensity.

4. Intensity

Dependence: The intensity of light determines the number of photons, and

thus the number of emitted electrons, but not their individual energies. This

explains why increasing intensity increases the number of electrons but not

their maximum kinetic energy.

Einstein's photon theory provided a complete and

accurate explanation of the photoelectric effect, aligning perfectly with

experimental observations. It also marked a significant step in the development

of quantum mechanics, challenging the classical wave theory of light and

introducing the concept of wave-particle duality. For this work, Einstein was

awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 (overlooking his vastly more important

contributions through Relativity). The photoelectric effect remains a

cornerstone of modern physics, demonstrating the quantized nature of

light and energy.

Before discussing Einstein’s other significant contributions

to quantum physics let us look at the man and the times he lived in.

Early Life

Albert Einstein was born on March 14, 1879, in Ulm,

Germany, to a Jewish family. His father, Hermann Einstein, was an engineer and

businessman, and his mother, Pauline Einstein, was a pianist. As a child,

Einstein was curious but slow to speak, leading his parents to worry about his

intelligence.

At age 5 (see his stunningly handsome picture below), young Einstein was fascinated by a pocket compass his father showed him, sparking his lifelong interest in physics and unseen forces. By age 10, he was deeply influenced by science and philosophy books, including works by Euclid and Kant. Both his looks and his academic interests stayed with him well past his most productive period in life.

Einstein attended Catholic elementary school in Munich but struggled with its rigid, discipline-focused system. At Luitpold Gymnasium (now Albert Einstein Gymnasium), he excelled in mathematics and physics but disliked rote learning and strict teachers.

In 1894, his family moved to Italy, but Einstein

stayed behind to finish school. In 1895, at 16, he failed the entrance exam for the

Swiss Federal Polytechnic School (ETH Zurich), doing well in mathematics and

physics but poorly in languages and other subjects. He then attended Aarau

Cantonal School (Switzerland) to improve his grades.

In 1896, at age 17, he passed the entrance exam and

joined ETH Zurich, where he later studied physics and mathematics.

He disliked formal lectures and often skipped classes,

preferring to study independently. His classmate Marcel Grossmann (who later

helped him with advanced mathematical concepts) took notes for him.

Despite being brilliant in mathematics and physics, he

was seen as a rebellious student who questioned his professors. In 1900, he graduated

with a diploma in physics and mathematics, but his unconventional approach made

it hard for him to secure a job in any academic position after graduation. He

worked as a private tutor in mathematics and physics for students.

Unable to secure any job suited to his capabilities, Einstein began work as a lowly patent examiner (see picture below) in Bern, Switzerland. However, this job gave him opportunities and time for pursuing his academic interests and set in motion the avalanche of new ideas that were to light up the world of physics, producing some of his most groundbreaking work, including his annus mirabilis papers of 1905, which addressed the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, and special relativity. These papers eventually established Einstein as a leading figure in theoretical physics and set the stage for his later contributions to quantum theory.

Einstein as a patent office clerk

Contrasting strongly with his world-famous public

image, Einstein’s personal life was complex and often troubled, particularly in

his relationships with his family. Einstein married Mileva Marić in 1903, a

fellow physicist and one of the few women studying science at the time. Their

marriage became strained due to Einstein’s increasing focus on his work and

reported emotional detachment. The marriage ended in divorce in 1919, with

Einstein agreeing to give Mileva his (anticipated) Nobel Prize money as part of

the settlement.

Einstein and Mileva had two sons, Hans Albert and

Eduard. Hans Albert Einstein became an engineer, but his relationship with his

father was often distant. Eduard Einstein suffered from schizophrenia, leading to

hospitalizations. Einstein deeply regretted being unable to care for him,

especially after leaving for the USA in 1933.

Wife Mileva and sons

Einstein later married cousin Elsa in 1919, but their relationship was also troubled.

Before marrying Mileva, Einstein and Mileva had a

daughter, Lieserl, born in 1902. Little is known about her fate, but some

reports suggest she may have died of illness or was given up for adoption. Einstein

never publicly acknowledged her existence, and details emerged only through

letters discovered much later.

Einstein as a public figure

Albert Einstein’s fame as a public figure extended far

beyond his scientific achievements. He became one of the most recognizable and

influential intellectuals of the 20th century.

An iconic picture taken on a historic occasion placing

Einstein where he belongs!

Einstein’s global fame exploded in 1919 when a solar

eclipse experiment confirmed his General Theory of Relativity. British

astronomer Arthur Eddington led the expedition that showed light bending around

the sun, proving Einstein’s General Relativity based predicts correct. Headlines

like “Revolution in Science – Newtonian Ideas Overthrown” (The Times, UK) made

Einstein an overnight celebrity. He became a household name, appearing on newspaper

covers worldwide.

Unlike most scientists, Einstein actively engaged with

the press and the public, explaining complex theories in simple, quotable

terms. His wild hair, thoughtful expression, and informal attitude contributed

to his public image as a genius.

Initially Einstein opposed World War II but later

supported efforts to stop Nazi Germany. A Jewish scientist, he fled Germany in 1933 as Hitler

rose to power. He spoke out against both fascism and anti-Semitism.

In 1939, Einstein signed a letter to US President

Franklin D Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might develop nuclear weapons. This

historic letter led to the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb

and its fearful aftermath.

Einstein’s photon theory was a radical departure from classical wave theory and marked a significant step toward the development of quantum mechanics. However, Einstein’s relationship with quantum theory was complex. While he recognized its empirical success, he was deeply troubled by its philosophical implications, particularly the probabilistic and observer-dependent nature of the Copenhagen Interpretation spearheaded by his friend and intellectual rival Niels Bohr.

The Copenhagen Interpretation and Einstein’s

Skepticism

The Copenhagen Interpretation, formulated by Niels

Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in the 1920s, became the dominant framework for

understanding quantum mechanics. It postulates that particles do not have

definite properties until they are measured, and that the act of measurement

itself affects the system being observed. This interpretation embraces the

probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, rejecting the prevailing deterministic

worldview of classical physics (to be discussed in more detail in the next article

of this series).

Einstein was deeply uncomfortable with the Copenhagen

Interpretation. He famously declared, "God does not play dice with the

universe," expressing his belief that the universe operates according to

deterministic laws, not probability. Einstein’s skepticism was rooted in his

realist worldview, which held that physical reality exists independently of

observation. He could not accept the idea that the act of measurement could

fundamentally alter the state of a system.

The Einstein-Bohr Debates

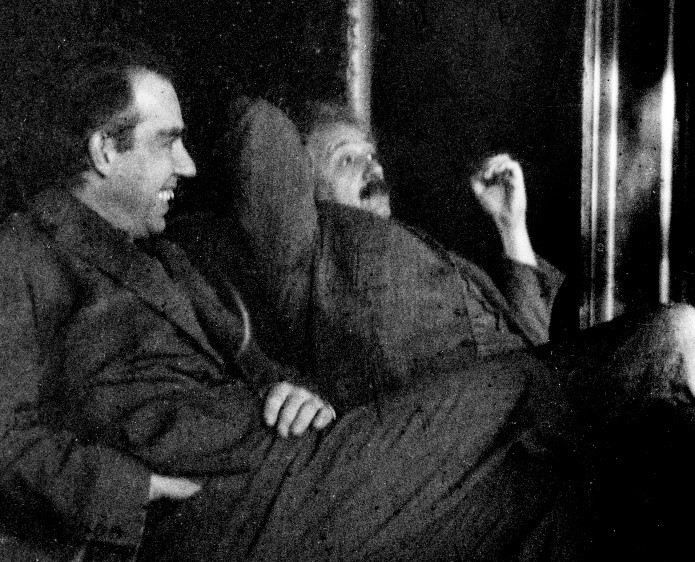

Einstein’s challenges to the Copenhagen Interpretation were most vividly expressed in his debates with Niels Bohr (see the picture below of the two together). These intellectual exchanges, which took place at the Solvay Conferences and other scientific gatherings, are among the most famous in the history of physics. Einstein devised a series of thought experiments to demonstrate the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, arguing that the theory failed to provide a complete description of physical reality.

The EPR Paradox

One of Einstein’s most notable challenges was the EPR

paradox, formulated in 1935 with his colleagues Boris Podolsky and Nathan

Rosen. The EPR paradox highlighted the phenomenon of quantum entanglement, in

which the properties of two particles are correlated in such a way that

measuring one particle instantaneously affects the other, regardless of the

distance between them. Einstein argued that this "spooky action at a

distance" violated the principle of locality, which states that physical

processes occurring at one location do not depend on the properties of objects

at other locations. He concluded that quantum mechanics must be incomplete, as

it could not account for these correlations without invoking non-local effects.

Bohr, however, defended the Copenhagen Interpretation,

arguing that quantum mechanics provided a complete and consistent description

of reality, even if it departed from classical intuitions. The EPR paradox

ultimately led to the development of Bell’s theorem and experimental tests of

quantum entanglement, which confirmed the non-local nature of quantum mechanics

and supported the Copenhagen Interpretation. Rather paradoxically, the EPR paradox

proved to be the death knell of the deterministic view that Einstein had so

strongly championed.

Einstein’s Later Years and Legacy

Despite his skepticism, Einstein’s contributions to

quantum physics were foundational. His work on the photoelectric effect and his

insights into quantum entanglement remain central to the field. However,

Einstein’s later years were marked by his pursuit of a unified field theory,

which sought to reconcile quantum mechanics with general relativity. This

endeavor, though ultimately unsuccessful, reflected Einstein’s unwavering

commitment to a deterministic and unified understanding of the universe.

Einstein’s challenges to the Copenhagen Interpretation

also had a lasting impact. His critiques spurred further research into the

foundations of quantum mechanics and inspired the development of alternative

interpretations, such as the many-worlds interpretation and pilot-wave theory.

While the Copenhagen Interpretation remains the most widely accepted framework,

Einstein’s questions continue to provoke debate and exploration.

Einstein’s Other Contributions to Quantum Physics

Wave-Particle Duality (1909-1916)

Einstein was among the first to argue that light has

both wave and particle properties, foreshadowing Louis de Broglie’s

wave-particle duality principle. This will be elaborated in a future article. His

work helped establish the foundation of quantum field theory.

Einstein Coefficients and Quantum Transitions

(1917)

Einstein introduced coefficients that describe

how atoms absorb and emit radiation. These coefficients played a major role in

quantum electrodynamics and the understanding of atomic transitions, besides paving

way for the invention of the laser that happened much later.

Bose-Einstein Statistics and Bose-Einstein

Condensate (1924-1925)

Collaborating with Satyendra Nath Bose (see my

earlier article on Bose and this historic collaboration),

Einstein extended quantum statistics to particles which later came to be known

as bosons. This led to the prediction of Bose-Einstein condensation, where

particles occupy the same quantum state at extremely low temperatures. This

phenomenon was experimentally confirmed in 1995.

Today, Bose-Einstein Condensate (BEC) is

recognized as a state of matter in which separate bosonic atoms or subatomic

particles, cooled to near absolute zero temperature, coalesce into a single

quantum mechanical entity on a near-macroscopic scale. This form of matter was predicted

by Einstein in 1924 on the basis of the quantum formulations of Satyendra Nath

Bose, foreshadowing the development of Bose-Einstein Statistics applicable to all

bosons.

Historical Significance of Einstein’s Quantum

Contributions:

1. Advancing Quantum Mechanics

Einstein’s work on the photoelectric effect

and wave-particle duality was pivotal in the early development of quantum

mechanics, laying the groundwork for quantum field theory, quantum

electrodynamics, and solid-state physics.

2. Quantum Technologies

His discoveries directly influenced modern

technologies, including semiconductors, lasers, and quantum computing. The

photoelectric effect is fundamental to solar panels, while Bose-Einstein

condensation has applications in quantum simulations and superconductivity.

3. Inspiring the Quantum Revolution

Though Einstein resisted the Copenhagen

interpretation, his challenges forced physicists like Bohr, Heisenberg, and

Schrödinger to refine quantum mechanics, leading to quantum mechanics'

probabilistic framework and further advancements in quantum field theory.

4. Quantum Entanglement and Modern Physics

Einstein’s scepticism about quantum

entanglement ultimately led to its experimental verification, which underpins

modern quantum information science, including quantum cryptography and quantum

computing.

Conclusion

Einstein's contributions to physics

transformed our understanding of the universe, from relativity to quantum

mechanics. His work on the photoelectric effect launched quantum mechanics,

while his debates with Bohr shaped its interpretation. Despite his discomfort

with quantum mechanics' indeterminacy, his insights led to foundational

developments in quantum physics and modern technology. Today, his contributions

continue to influence cutting-edge research in cosmology, particle physics, and

quantum computing, making him one of the most significant figures in

scientific history.

The bottom-line

Einstein’s

image as a "quirky genius" is still widely used in pop culture. The

famous E = mc² equation became symbolic of genius itself. In this article, the

focus has been on a slightly less well-known equation E = hν that opened up

another face of this genius.